Lancaster ME699 - A Bomber crew at war

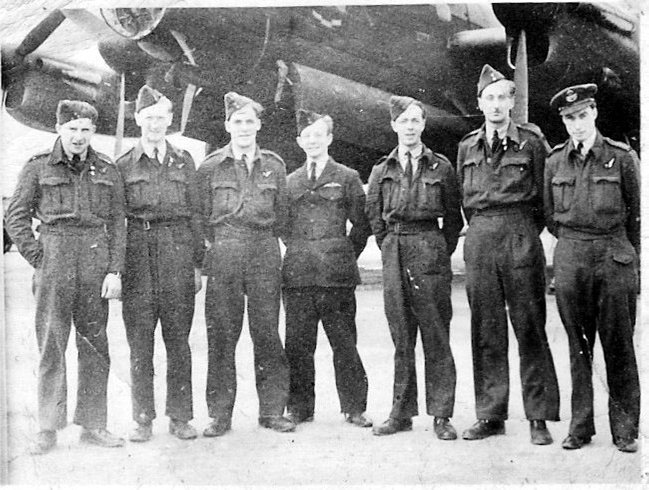

Left to right: Flight Engineer Sgt William (Bill) Robinson, Wireless Operator Sgt Thomas (Leslie) Jackson, Bomb Aimer F Sgt John (Jack) Wainwright, Pilot Officer William (Bill) Young RAAF, Rear Gunner Sgt Robert (Bob) Routledge, Mid Upper Gunner F Sgt William (Bill) Rennie RCAF and Flying Officer Frank Wareham, Navigator.

Not pictured from the crew lost on the 4th/5th July are Flying Officer Harold Braathen RCAF, who was a second navigator, flying for experience on that particular night, and Rear Gunner Sgt Ronald Houseman who took over from the regular rear gunner, Bob Routledge when he was taken ill shortly before the aircraft took off.

William Young's Crew

My father John "Jack" Wainwright was posted to 82OTU (Ossington - September to November 1943)) and there he was crewed together with Aussie pilot Bill Young, navigator from London Frank Wareham, and fellow Tyke's Thomas (Leslie) Jackson (W/Op) and Bob Routledge (AG). At 1657HCU (Stradishall - February 44) and 5LFS (Waterbeach - March 44) the five became seven with the addition of Flight Engineer Bill Robinson and Canadian mid upper gunner, Bill Rennie. In early March 1944 the crew was was finally posted to No. 51 Base (Swinderby) qualified for allocation to a squadron.

Bill Young's crew was posted to 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron stationed at Dunholme Lodge in Lincolnshire on the 24th March 1944. 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron was part of 5 Group, Bomber Command, and back in December 1941 had been the first squadron to be equipped with the Avro Lancaster.

Tour of Duty

The crew joined 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron in some of the busiest months of the war for Bomber Command, preparing the way for the D-Day invasion in June, and then afterwards supporting the troops on the ground and countering the V1 menace. Statistics show that the months of June and July 1944 saw the heaviest casualties of the whole of WWII for Bomber Command (see Rob Davis' RAF Bomber Command 1939-45 for details).

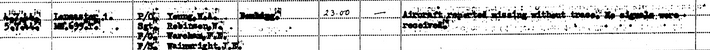

Henry Horscroft of the 44 Squadron Association has provided me with a list of the crew's missions up to and including the night of the 4th/5th July 1944 . All were flown in Lancaster Mk I, ME699, KM-T for Tommy.

The operations are listed here, and further details of the individual raids and targets and some pictures of damage inflicted can be found in the diary section of the RAF Bomber Command History site.

After a few days of circuits and landings, an overnight "Bullseye" training flight, and an operational flight with experienced crews for Bill Young and Frank Wareham, Flight Sergeant Bill Young's crew was briefed for its first operational mission, an attack on Nuremberg. This was the final fateful act of Bomber Harris's "Battle of Berlin", an attempt to destroy German morale by battering it's cities night after night, before the main force was redirected onto missions to support Operation Overlord, the invasion of Europe.

That first mission on the night of the 30th March 1944 was a major disaster for Bomber Command with 95 aircraft, 11.9% of the force, shot down as a clear moonlit night turned the raid into a turkey shoot for German fighters, 82 aircraft were lost before they reached the target. The loss was the worst suffered by Bomber Command on a single raid during the whole of WWII. 44 Squadron was lucky to only lose two aircraft in the raid.

As a new crew on their first trip my Dad's crew will have been very lucky not to be lost as so many "green" crews were. Even so, Bob Routledge noted in his logbook that the arircraft was hit by incedaries dropped from another aircraft above them, and attacked by a Junkers 88 nightfighter in the clear, moonlit skies. The fact that he could state the aircraft type that attacked them shows how good visibility must have been and what a close shave it probably was.

Rob Davis says at RAF Bomber Command 1939-45, "During the first five operations the new crew ran ten times the risk of the more experienced men, simply because they did not know the ropes. Having survived 15 ops, the odds were reckoned to be even."

Over the following three months they flew regularly attacking mainly targets in France, paving the way for the invasion in June. The full list of operations flown by the crew, including excerpts from the Squadron Operations Record Book (ORB) are here.

In May the crew flew on 11 nights including another tragic mission, the attack on Mailly le Camps on the 3rd of May when again over 11% of the attacking force were lost. this happened when US Forces radio interference meant that the Master Bomber could not order the attack, leaving the main force circling the target. There were several collisions and night fighters also infiltrated leading to a loss of 42 aircraft.

On the night of 21st June 1944, 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron put up sixteen aircraft including the now Pilot Officer Bill Young's crew in KM-T on a raid to attack a synthetic oil plant in Wesseling, near Cologne in the Ruhr. Six of the aircraft failed to return, a loss of 37 men. 619 Squadron, which shared Dunholme Lodge with 44 also lost six aircraft as did 49 Squadron based at Fiskerton, five miles away. Altogether 37 Lancasters were lost in the raid out of 133 dispatched, 27.8% of the force. This was by far the highest percentage loss on a single raid by Bomber Command after February 1942.

The 207 Squadron Association website has a detailed set of pages on the Wesseling raid which include a target map and details of the equipment and tactics of the RAF and Luftwaffe during the raid. It also carries narratives from some of the 44 Squadron survivors and a Roll of Honour for the crewmen lost by the Squadron on the raid.

The aircraft was damaged three times while Bill Young was flying it, before it was finally shot down in July. The crew took part in twenty-one missions, and were three times told to abort while over their target due to poor visibility. Attacks on French targets were abandoned unless the target could be seen clearly to avoid civilian casualties.

By the time July came round Bill Young's crew would have been viewed as veterans, even though their skipper was just 21. My Dad was three weeks short of his 21st birthday.

4th July 1944

On the night of 4th July the crew of Lancaster Mark I ME699, designated KM-T for Tommy, took off from Dunholme Lodge at 23:00 as part of the raid on St Leu d'Esserent.

The crew of KM-T that night were:

P/O William Young, RAAF - Pilot

F/O Harold Braathen, RCAF - Navigator/2

F/Sgt John Wainwright - Bomb Aimer

Sgt William Robinson - Flight Engineer

Sgt Thomas Jackson - Wireless Operator

F/Sgt William Rennie, RCAF - Mid-upper Gunner

Sgt Ronald Houseman - Rear Gunner

F/O Harold Braathen (left) was a new addition to 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron having been posted in with his own crew, skippered by Flight Sergeant Donald Lade, on 30th June 1944. He was sent up with Bill Young's crew as it was the practice for new Pilots and Navigators to be sent out with an experienced crew to get a feel for what flying operationally was all about. Bill Young and Frank Wareham had done the same on the 26th March 1944.

The regular rear gunner for the crew, Bob Routledge, should have flown that night but was taken ill at the last minute was sent to hospital after a pre-flight medical check and replaced by Sgt Ronald Houseman (right) for whom it was actually only his third mission, being the regular mid-upper gunner for F/O Carnegie and having completed ops with him on the 24th and 27th June 1944.

I wonder what the crew felt ahead of the mission on the 4th July 1944. Up to that point they had completed all their operations as a tight group of seven and, while they had experienced a few scrapes, had come home safely every time. That night they had a new rear gunner and a "passenger" on board.

It is well known that Bomber Command crews were massively superstitious.

Wikipedia says of this: Many biographies and auto-biographies of aircrew record that facing a very limited life expectancy airmen frequently adopted mascots and superstitions, holding to a belief that if they adhered to a particular custom or carried a specific talisman with them, then they would "get home in time for breakfast".

Amongst those frequently mentioned are having a family photograph attached to their crew position inside the bomber, carrying a rabbits foot or teddy bear, wearing a particular scarf around the neck, urinating on the tail wheel of the aircraft before take off, or always donning their flying kit on the same sequence. Such rituals were taken extremely seriously. Having to fly in an unfamiliar bomber was highly unpopular, if a crew had a particular aircraft regularly assigned to them many considered it unlucky to have to fly in another if their own was unserviceable.

Either flying as a "spare bod" to cover for sickness in another crew or having a "spare bod" fly in their own crew was not popular. Many crews were extremely tightly-knit and would not consider being unable to fly as a complete crew, if a crew member was not fully healthy quite often he would still fly in order to keep the crew together, believing that their absence might cause the loss of their crew on that night. The fear was not groundless as a newly arrived airman from a training unit might be used as a temporary replacement for their highly experienced crewman and a momentary hesitation in calling for evasive action in a pending night-fighter attack did result in bombers being lost.

That Bill Young's by then experienced crew were lost that night will only have strengthened the conviction that any change of personnel was unlucky to those back at Dunholme Lodge that had known them.

For Bob Routledge, once recovered from his illness, it was a case of survivors guilt. Bob subsequently completed his tour of operations with other crews and often wondered whether he would have spotted the fighter that shot KM-T down given his extra experience. If he had been fit to fly that night would his mates have survived? Was it all his fault?

Bob's family told me that he said he always had Bill Young weave the aircraft so that he could watch for night fighters approaching from below, a favourite tactic for "Schrage Musik" fighters, which had guns that pointed upward. Ronald Houseman was green, and had been a mid-upper gunner by trade.

KM-T Shot Down

It is believed that KM-T was the fifth Lancaster downed by German night fighters on the raid on St Leu d'Esserant when it was shot down by a ME 110 night-fighter over Beauvais. The German night fighter claim for KM-T states the time of the kill as 01:49 on the 5th of July 1944, and names the pilot of the aircraft as Unteroffizier Günther S. Schlomberg (also see Kracker Luftwaffe archive)..

Schlomberg was with 3./NJG3, a night-fighter unit based in Vechta in northern Germany. German controllers had directed the night-fighters to the channel on detecting the raid coming in and the fighters followed the bomber stream across France and towards their target. At some point after the St Leu bombers attacked their target and turned for home Schlomberg attacked KM-T while it was flying at 2,500m above Beauvais.

German records show that Unteroffizer Günther Schlomberg was killed and Unteroffizer Otto Wagner was wounded when their aircraft crashed near Cruxhaven. near Hamburg on a training or equipment check flight, on 11th August 1944. The cause of the crash is not known. Their aircraft when they crashed was Bf110 G-4, D5 + LL, works number 140339.

With ME699 fatally hit by Schlomberg's night fighter shortly after dropping its load of 1,000lb bombs on target, the pilot, Pilot Officer Bill Young ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft. The hatch at the front of the Lancaster was right below the bomb aimer's position and on such an order the bomb aimers job was to open the hatch and get the hell out, making space for the rest of the crew.

Jack was first out, followed by the flight engineer Sergeant Bill Robinson. It seems that wireless operator Leslie Jackson may also have bailed out but did not survive, before the plane plunged to the ground in the southern end of the small hamlet of Laversines, between Beauvais to the west and Bresles to the east and exploded, killing the other men still on board.

The aircraft came down in an orchard about 100 yards behind the home of Monseiur Bole in Laversines. The only body identified by the German's was that of Leslie Jackson, who was buried in the local military cemetary, Marissel, with some of the other unidentified remains from the crash site. Mr Bole also buried some remains in his garden, and the crew was only reunited and buried together after the war.

It would seem that there was some confusion whether another of the crew bailed out and had been taken prisoner, possibly caused by Leslie Jackson getting out of the aircraft, and this is referenced in letters sent by Canadian authorities to the Rennie and Braathen families (see their specific pages on this site). It may have been that my father and Bill Robinson said that they had seen another bail out, although this is not referenced in the IS9 report filed on my father's return to the UK.

Bill Robinson's IS9 report is missing from the Archives.

Leslie Jackson's family believed that he survived the jump, but his parachute was caught in a tree and he was shot there. I have found no evidence for this having happened, but would like to hear from anyone who has any evidence either way as to what exactly happened to Sergeant Jackson.

The six crewmen that did not survive are buried in a single grave in the Marissel French National Cemetery in Beauvais. Sergeant Ronald Houseman, Air Gunner, is also commemorated on the War Memorial at Fewston in Yorkshire.

Jack Wainwright and Bill Robinson were picked up by the French Resistance (actually the local police in Bresles) and hidden, initially together, waiting for Allied troops to reach the area.

At some point the men were separated with my father being sent to the Pelletier family in Haudivilliers and Bill Robinson sent elsewhere, I believe to a family "Morels" in Angicourt, near Clermont.

Both eventually made it home to the UK after US forces came through the area at the end of August 1944. The details of my father's time in France is here.

Bill Robinson 's story has been much more elusive to find and if anyone knows what became of him, I would be very interested to hear from you.